Authoring Our Own Stories Through the Power of Creative Thinking

2023-05-09

By Sandra Vacciana, National Lead for Authoring Our Own Stories, Partnership for Young London.

Authoring Our Own Stories is a national youth recovery project, co-produced with young people aged 13 to 25, which examines the influence young people’s civic or social identities have on their access to youth services. The project is funded over five years by the National Lotteries Community Fund, and we have just completed our first year!

Four youth units were involved in this initiative. Each group worked with a specific demographic of young people to deliver a regional research project on civic identity; Partnership for Young London and Youth Focus Southwest worked with young Black and Brown people from urban and rural areas respectively; Youth Focus Northwest worked with young people from areas directly affected by the ‘Levelling Up’ agenda; Yorks and Humber Youth Work Unit worked with young people who identified as having Special Educational Needs (SEND).

Below, I reflect on some of the creative methods young people and colleagues used to develop their regional projects, and the value I believe this approach has added to our research process.

Wicked Ideas

My colleagues and I soon recognised that ‘Authoring Our Own Stories’ had gifted professionals and young people alike with an infinite list of ‘wicked problems’ (Cox et al, 2021). Wicked, as in ‘interesting and cool’ but also wicked as in ‘complex, multifaceted, paradoxical’ and therefore hard to resolve (Rittel and Webber, 1973). Authoring one’s story required trust, time, and a range of resources that would capture the authenticity of young people’s voices. As creative approaches can be playful and exploratory by nature, they allow the mind to open up, tap into the subconscious, and potentially allow new ways of thinking about an idea to emerge. (Gauntlett, 2007). Therefore, coupled with conventional research methods, we felt a creative approach could enrich outcomes and capture insights that remained true to the experiences of the young people who had shared them.

Defining Our Practice

Our first step as Regional Leads was to form a steering group to lay the foundations for the work ahead. We acknowledged quickly that it could be a big ask for people of any age to share experiences related to identity. So, we tried and tested activities we hoped to deliver as a group first, before approaching this work with young people. At times, I found expressing my own experiences quite testing - I learnt that I’m not that keen on feeling vulnerable! What enabled me to be more open was that visceral ‘aha’ moment, when others felt brave in sharing how their identities shaped how they or others perceived themselves, and the rich discussions that followed. This approach reassured us that our methodology would serve our project aims.

Modelling Our Practice

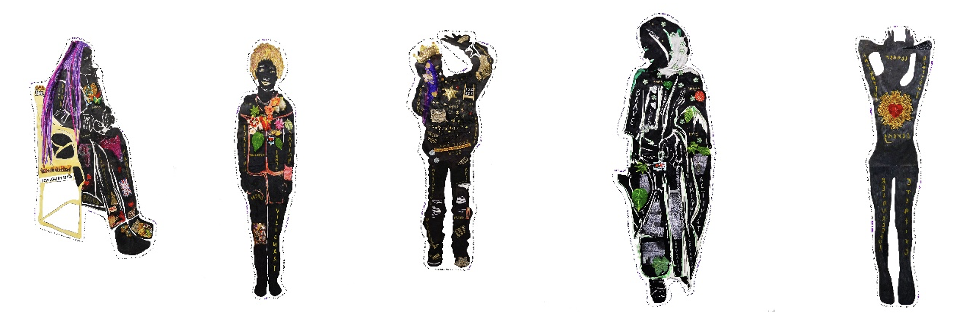

Each region recruited cohorts of five young people through its local networks to become Young Leaders. Group members came into the process as ‘Experts by Experience’; having a set of skills they were willing to use as a resource for social change (Sandhu, 2017), and we sought to support their existing skills and nurture new ones. Young Leaders were positioned as ‘knowledge-holders’ and we, the Regional Leads, ensured that we worked alongside them to enable a mutual exchange of ideas to produce this work. As a result of this principle, the power dynamics were flexible, which allowed co-production to evolve in a supportive, responsible, equitable, and transparent way.

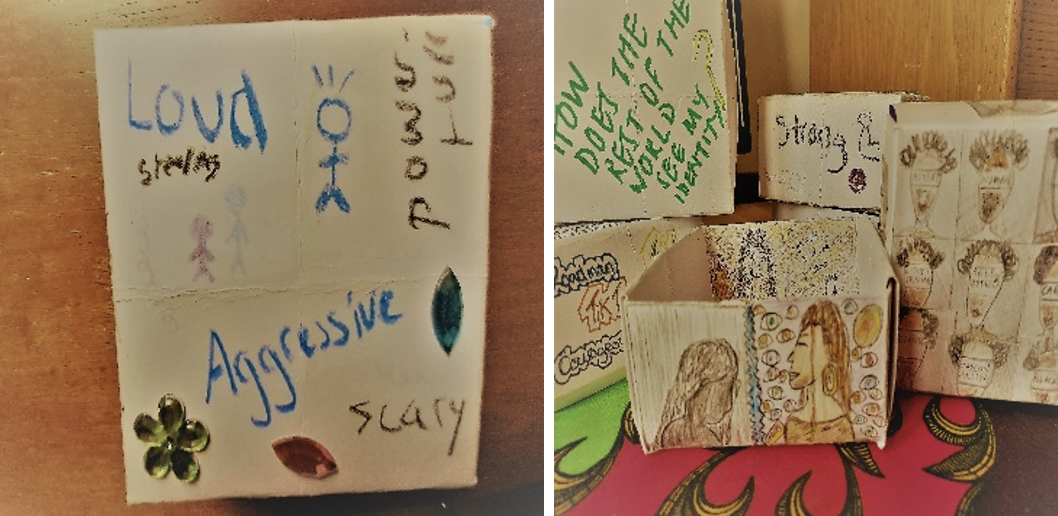

Sometimes words unleash creativity but, in research, they can be confining. Using simple creative approaches such as drawing, creative writing, and handicrafts as part of our methodology allowed Young Leaders more room to respond to the questions they were being asked. We valued conventional methods of investigating ideas about civic identity but wanted to provide the opportunity to explore intuitive, raw, less tempered thoughts and feelings too. This helped build skills and gave Young Leaders more confidence to express themselves without censorship.

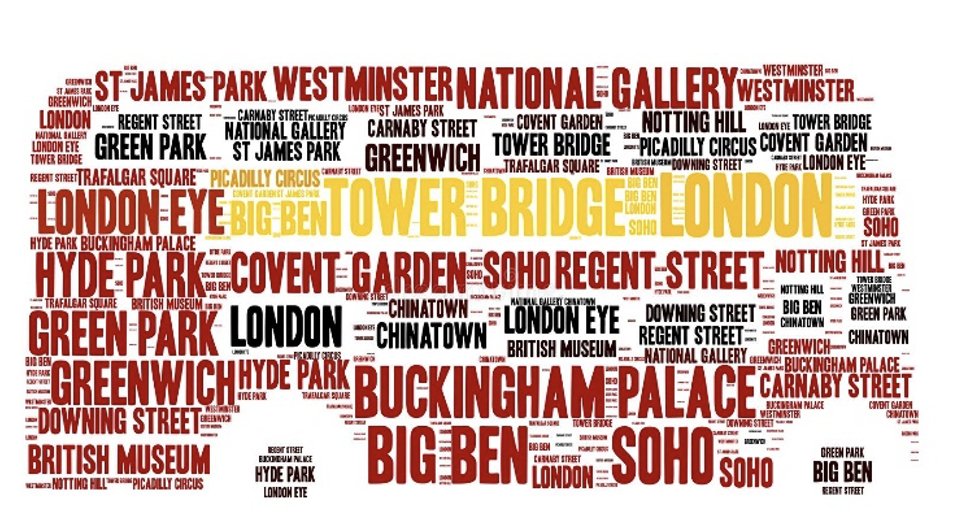

Creativity permitted our minds to wander and examine questions from another perspective. This engaged our brains in a different way, and opened channels of exploration that may have remained closed had we simply asked the question in an interview or survey format (Gauntlet, 2007). Using different stimuli expanded the group’s propensity to find solutions that spoke to the basis of this project – increasing access to youth services for minoritised young people. Sometimes the process itself was more important than the outcome and at other times vice versa. In the initial stages of exploring understanding of the term identity, we asked Young Leaders to commit pen to paper in a stream of consciousness and write whatever sprung to mind for a couple of minutes using ‘Identity is…’ as the starting point for the exercise. Chriese [Young Leader] wrote:

Identity is…

Me as a whole

Not just my name

My place of birth

My age

My height

And ethnic group -

Check my passport for that!

Identity is what I want it to be

Not what you see me to be

“In our group, Young Leaders used photography to showcase their employment aspirations, hobbies, where they feel safe, and how they feel perceived by society at large.” said Chelsea Jackson, Regional Lead for Yorks and Humber. “Many identified that they hide their disability when outside of groups they feel comfortable in, while some shared that they weren’t given opportunities or the skills and knowledge to develop their civic identity. This highlighted the difference between activities that kept them occupied and activities that gave them life skills and encouraged aspirations.”

Creative approaches also offered a means to build safe environments before delving into hard topics. We used an origami activity to create paper boxes, where making the time and space to create together and chat helped us to feel more connected to one another and break down walls. Working in this way helped us to then have highly sensitive and difficult conversations about the often racist, sexist, and ableist ways group members felt their civic identities were viewed by society.

What is Next for Authoring Our Own Stories?

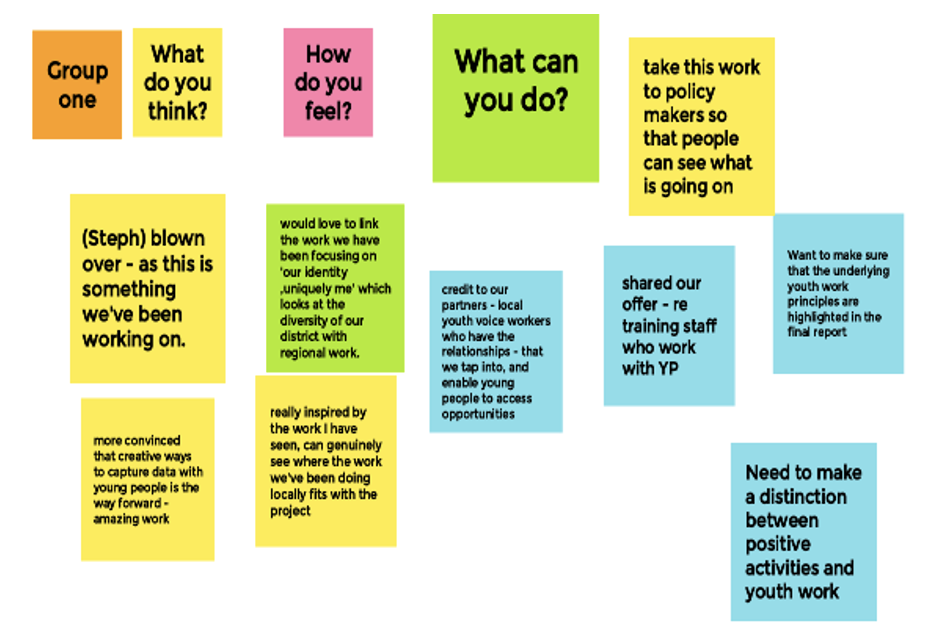

Young Leaders from across the regions co-facilitated a roundtable event at the end of our first year, where guests were invited to consider how they will use learning from the project in their own areas of work. We are in the process of following up the pledges from the roundtable to see what progress has been made and additionally, are building regional partnerships to identify how we can apply learning from year one at a local level.

Year two will involve working with new cohorts of young people from across the four regions, and we will continue to adopt creative approaches throughout each stage of the research process. This will, we believe, provide the optimum potential for young people to share stories of their lived experience - growing up in an environment feeling overlooked and under-served.

Shaking loose habits of mind and behaviours is hard, but challenging institutional constructs that constrain understanding of social and civic identities? Harder still. Young people from minoritised communities are discriminated against daily because of who they are and where they come from. Finding solutions to entrenched views will be an iterative process but that doesn’t mean it can’t be a creative one. ‘Authoring Our Own Stories’ places creativity at the heart of addressing these endemic issues because we believe this approach, in its broadest sense, offers potential for new insights to be developed within the research process. Adopting a creative approach need not require training or hi-tech resources. Simply asking ‘how else might we explore this?’ could unlock different solutions to enduring social problems and stimulate opportunities for new mechanisms to challenge inequality. This is what is needed to stem the life-limiting outcomes that are the inevitable consequence of entrenched discrimination.

--

For more information about 'Authoring Our Own Stories' contact sandra.vacciana@cityoflondon.gov.uk or visit Authoring Our Own Stories| PYL (partnershipforyounglondon.org.uk)

_ _

References

Cox, R. Heykoop, C. Fletcher, S. Hill, T. Scannell, L. Wright, L. Alexander, K. Deans, N and Plush, T. (2021) ‘Creative action research’. Educational action research. 29 (4), pp. 569-587.

Available at: DOI: 10.1080/09650792.2021.1925569 (Accessed January 2023) Gauntlett, D. (2008) Creative explorations

Available at: Representing identities (part 1: method) - YouTube (Accessed January 2023)

Rittel, H. and Webber, M. (1973) What’s a wicked problem? Available at:What's a Wicked Problem? | Wicked Problem (stonybrook.edu (Accessed January 2023)

Sandhu, B (2017) The value of lived experience in social change: The need for leadership and organisational development in the social sector Available at: Summary vle (thelivedexperience.org) (Accessed: January 2023)