The alignment spiral: why talking about shared measurement sometimes feels like Groundhog Day

2025-07-11

Anna Waldie and Bethia McNeil, June 2025

When it comes to arguing for the value of greater alignment of evidence and data in the youth sector, you may (rightly) feel like we’ve been here before. But we haven’t just been here before, we arguably never left this particular conversation! As we progress towards the closure of YMCA George Williams College, one of the things that we have been reflecting on is why this theme is so enduring, and – if it’s so significant – why does it feel like we’re continuously circling back to the start? Why can’t we see more progress?

We know it isn’t for lack of effort – lots of intelligence, energy and resource has been thrown at this in a variety of guises.

So why, then, are we still having the same discussion we were having ten years ago (and probably before that)? And why does it keep feeling relevant?

We’re not sure there’s one answer to that question, but we have been reflecting on the nature of the youth sector as a system, what this means for conversations about ‘alignment’ and where these take us.

As part of the College’s role in convening the Youth Work Evidence Alliance, we’ve just finished our largest ‘listening exercise’ to date focused specifically on shared measurement, common outcomes, and alignment across data and narrative in youth work.

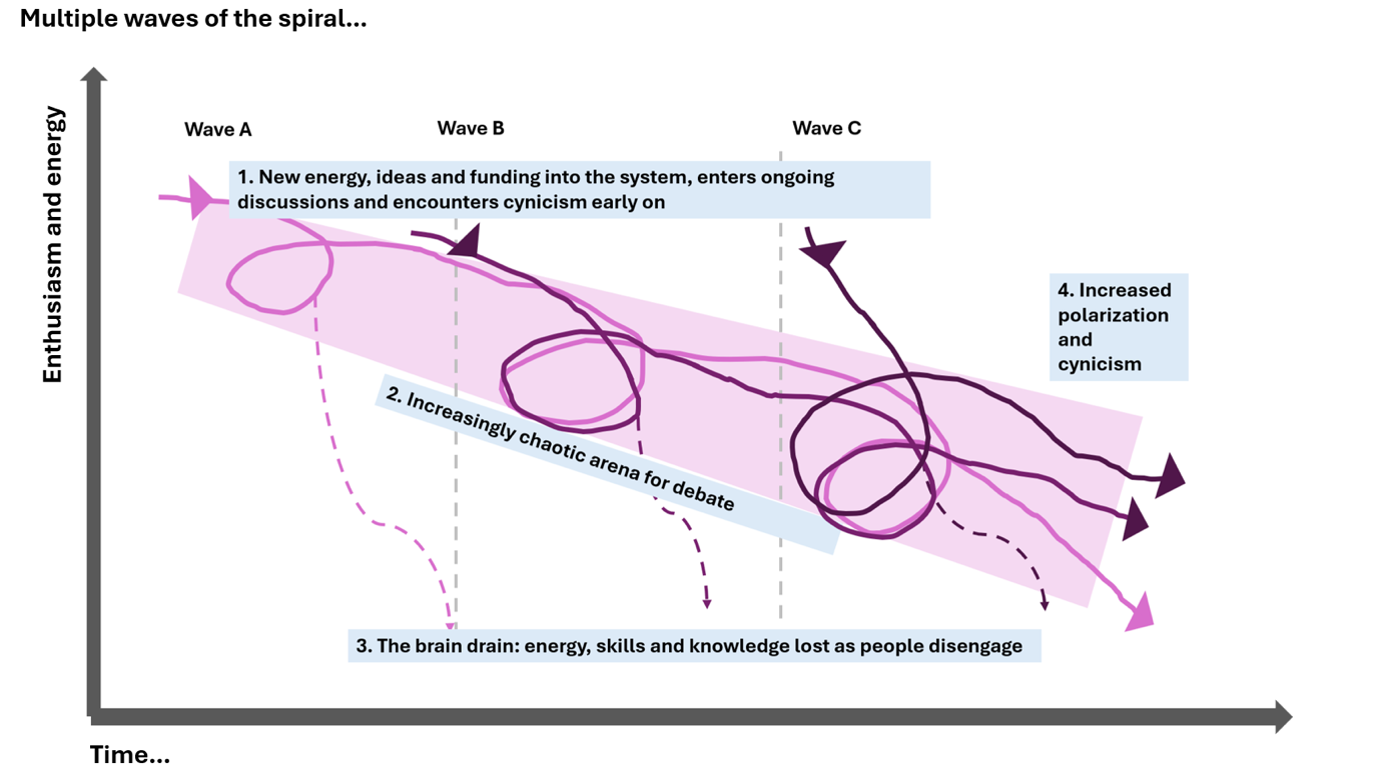

Here are some very draft ideas from our work about the enduring – and cyclical - nature of this discussion. We think they flow from one another and, over time, can create a spiral that sees us asking ourselves the same questions. Here’s what we see when we look at the youth sector as a system:

1. The youth sector feels like an embattled place to be: at worst, systematically deconstructed through the withdrawal of resources over the last 15 years; at best, profoundly neglected. There is a strong sense of youth work being ‘devalued’ as a profession, as a way of working, and as a right for young people;

2. Everyone working within the youth sector wants the sector (and their own work within it) to feel more secure, and is looking for ways to bring more money, respect and stability into the system. Alignment of data and evidence is seen as a strategically viable way to bolster the perceived value of youth work in wider society (including through evidence of impact, return on investment and shared narratives – this is an ideologically broad tent), which might leverage more resources into the system;

3. People across the system – funders, practitioners, commissioners, researchers - invest in exploring alignment of data and evidence. There’s no clear lead body or agency to corral these efforts, so they emerge organically and sometimes concurrently. Some efforts focus on alignment with a pre-existing approach or model, but many others begin with establishing something new, adding to an already crowded and confusing space;

4. But this investment is not universal, and neither is the energy all pulling in the same direction. Some don’t want to align, or may be able to accept alignment but only if it’s everyone else aligning with their way of doing things. Some have already invested in their own systems and don’t want to change. They may worry about sunk costs, or actually prefer to position themselves as unique. Others need more convincing that alignment will be worth it for them individually (even when they accept that it’s better at sector-level). Some are already aligning – but to lots of different things at the same time. Others are happy to align, but are waiting to see what’s the best thing to align with. Many (practitioners in particular) have been told they ‘should’ align but without the case being made for why they would intrinsically support it;

5. Those in roles with influence over the sector (trusts and foundations, for example, and policy makers) start to see the multiplicity of alignment efforts. They may be approached multiple times by different agencies or groups asking for support and endorsement. They may also begin to hear dissatisfaction and suspicion, and feel a strong desire not to wade in. And so they watch and wait, perhaps saying they’d prefer to be led by the sector;

6. And so, the uptake of ideas and actions is inconsistent, despite significant time and energy being expended – and not everyone is transparent about when, where or why they’re not engaging. Delivery organisations are concerned that they can’t see funders and policy makers endorsing particular approaches;

7. The sector is diverse, disparate and dispersed, meaning new ideas around alignment (which are not necessarily universally embraced in the first place) take longer to take root and gain traction - and even when ideas about alignment are shared or embedded, they remain in pockets across the system rather than centralised in system-wide institutional memory;

8. The competition that is both endemic and constantly reinforced across the sector rears its head, seeding mistrust and diffusing efforts to align. The conversation becomes about who gets to set the direction of alignment, rather than alignment itself. Alignment efforts themselves start to become misaligned, which in turn stokes the cynicism of those who feel like they’ve been here before;

9. The fragility of the sector means that those really committed to championing work on alignment are likely to get overcome by more pressing, existential challenges such as securing income or pivoting in response to policy or regime change, meaning they cannot continue their work (the College is an example of this);

10. The work loses momentum, stalls or disappears. Those who felt invested in the work feel frustrated, let down, and like their effort has been wasted. Those who were cynical say “I told you so”, those who were on the fence are less likely to engage in future;

11. It is unclear where learnings about alignment of data and evidence have been ‘stored’ in the sector, and how we signal where we have reached collectively. This can give people the sense that progress may have been made but learning is ‘patchy’ and hard to implement;

12. The sector still feels fragile. People continue to search for ways to make it feel more secure. Alignment continues to present an appealing solution to some, particularly if they are newer to the sector and have not seen previous efforts fail;

13. Some who have been working in the system for a while begin to feel fatigued by the cycle and there is a risk they will check out of alignment efforts, believing that they are not going to take hold – as they haven’t before. This means that those with the most knowledge and institutional memory take their valuable insight away into the ‘do not engage’ group (or worse, the cynics);

14. Others continue to champion alignment of evidence and data, but the ideas are entering into a more fraught emotional space, and may provoke more backlash or be open to fiercer criticism or disengagement from those who have engaged previously and feel they have not seen enough (or the right kind of) progress. But those newer to the system continue to bring hope, energy and new ideas, which keeps the conversation alive - although the questions being asked are often the same ones;

15. The spiral continues….

Some spirals are good. This happens when ideas, models and approaches are iterated through feedback and continuous reflection. But some spirals are more limiting, feeling more like we’ve become stuck in ever decreasing circles.

So how might be break out of one spiral and catalyse another? We’ve written up a range of thoughts and ideas that are published on our website, but in short we think some of the ways forward are to:

• Prioritise alignment over other things, so that it’s not as vulnerable to being pushed down the agenda

• Offer and accept leadership roles to bring alignment efforts together, and provide stewardship for learning and sharing

• Take an inclusive perspective on alignment, incorporating different perspectives on evidence, and on the degree of alignment

• Recognise that alignment might only ever apply to one area of your data and evidence gathering – and this is ok – it doesn’t have to be all or nothing

• Embed alignment into all funding and commissioning ‘pots’, even in a light-touch way

• Make data open by default (as far as is ethical and practicable) to increase the value of shared data sets

• Incentivise alignment in every way possible – celebrate, make space, platform, and reward.